Atomic Plants: Were they safe? ARE they safe?

[under construction]

First, it’s important to recognize that except for a few unusual lines of research, the atomic plants were *not* radioactive. They were mutated by radiation, but were not themselves a source of radiation. This is not a story about radioactive plants. It is a story about radiation-induced mutagenesis.

There is of course, a very long history of humans altering the genetic material of plants. Selective breeding is one example, with which we are familiar and of which we are unafraid.

But selective breeding is slow. In the twentieth century, there was an interest in speeding up the process by increasing the frequency of genetic variation. In theory, more mutations meant a better chance of *advantageous* mutations that could then be selected for breeding.

In a 2007 interview in the New York Times headlined “Useful Mutants, Bred with Radiation” Dr. Pierre Lagoda highlights a key difference between radiation-induced mutagenesis and *some* modern GMO techniques that would seek to combine genetic material from, say, a fish with that of a tomato: “I’m not doing anything different from what nature does. I’m not using anything that was not in the genetic material itself.”

That may be true, but it is also possible that the mutations induced by radiation are ‘scramblings’ that might never occur within the normal, random variation of the genome.

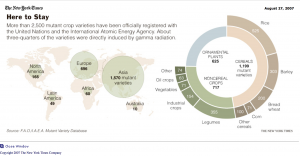

“Though poorly known, radiation breeding has produced thousands of useful mutants and a sizable fraction of the world’s crops, Dr. Lagoda said, including varieties of rice, wheat, barley, pears, peas, cotton, peppermint, sunflowers, peanuts, grapefruit, sesame, bananas, cassava and sorghum. The mutant wheat is used for bread and pasta and the mutant barley for beer and fine whiskey.

The mutations can improve yield, quality, taste, size and resistance to disease and can help plants adapt to diverse climates and conditions.”

If you’re wondering if you’ve ever consumed a grain, fruit, or vegetable that comes from an induced mutation, the answer is probably “Yes”. You might know that you have eaten a Rio Star graepfruit, or a “Gold Nijisseiki” Japanese pear. But you might be unaware that you’re consuming induced-mutation cultivars in the “Durum” wheat in your pasta, or the “Reimei” rice in your curry.