Government Gamma Gardens

“Atoms for Peace” was also, in a way, “Atoms for Jobs”. Jobs for scientists, and work for the national laboratories made redundant by the end of World War II.

The formal research efforts associated with the Atoms for Peace program meant completely new lines of investigation and funding for the nation’s official scientific sites like Brookhaven, Argonne and Oak Ridge, now turned to the uses of radiation for industry (x-raying for flaws in steel, for example), medicine (this is where ‘nuclear medicine’ begins), and agriculture (the gamma gardens).

But the stated purpose of “Atoms for Agriculture” was “Victory over famine”. Experimentation with the effect of X-rays on plant material in the 1920s had shown that they induced inheritable changes in barley. The atomic age now enabled the application of new ionizing radiations as mutative tools, in the hope that an increased rate of random mutations would find some scramblings of the genome that made the plant a stronger, faster, more disease-resistant version of its original self.

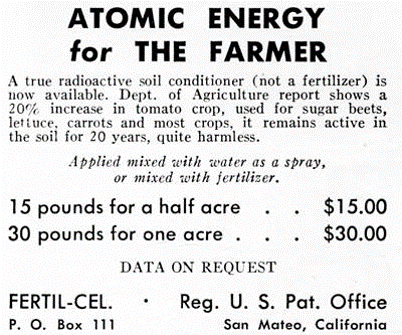

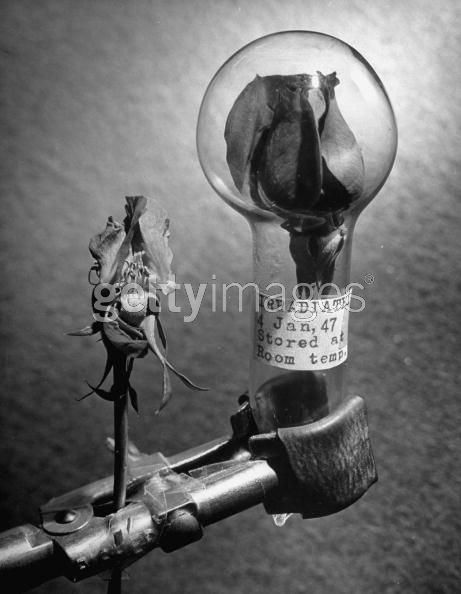

The term ‘atomic garden’ had first entered the English vocabulary in 1950; a reference to experiments at Argonne National Laboratories in Chicago in which plants breathed in in an atmosphere of radioactive carbon dioxide. There were also efforts to create fertilizers with radioactive tracers, and some rather frightening attempts at radioactive ‘soil conditioners’. But most botanic experimentation involved simply irradiating plants to induce mutations.

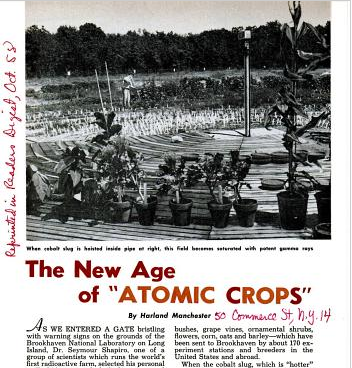

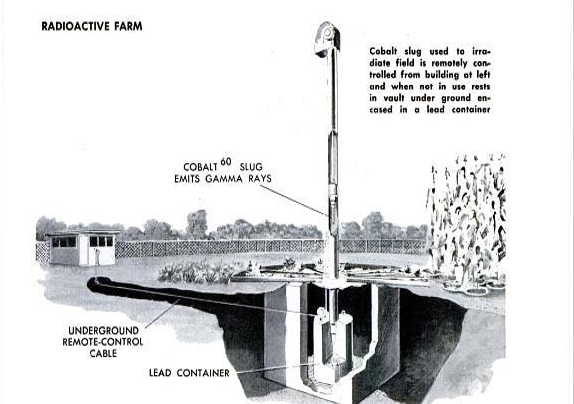

In the gamma-garden at Brookhaven National Laboratories in Rhode Island, established in 1949, plants and seeds had their genomes ‘rebuilt’ by being exposed to a cobalt-60 source rising totem-like from the centre of a field planted in concentric circles with plants ranging from strawberries to sugar maples. By 1958 atomic agriculture had been taken up in government laboratories around the world: Virginia, Florida, Wales, Sweden, Norway, Russia and Costa Rica, with others referred to as “under way”.

The circular spatial form of the gamma gardens, which in aerial view uncannily resembles the radiation danger symbol, was simply based upon the need to arrange the plants in concentric circles around the radiation source which stood like a totem in the center of the field. It was basically a slug of radioactive material within a pole; when workers needed to enter the field it was lowered below ground into a lead lined chamber. There were a series of fences and alarms to keep people from entering the field when the source was above ground.

The amount of radiation received by the plants naturally varied according to how close they were to the pole. So usually a single variety would be arranged as a ‘wedge’ leading away from the pole, so that the effects of a range of radiation levels could be evaluated. Most of the plants close to the pole simply died. A little further away, they would be so genetically altered that they were riddled with tumors and other growth abnormalities. It was generally the rows where the plants ‘looked’ normal, but still had genetic alterations, that were of the most interest. They were ‘just right’ as far as mutation breeding was concerned! A huge range of plant materials, from crops to ornamentals, were tested: peaches, grapes, blueberries, sugar maples, barley, corn, wheat, violets, gladiolus.

By 1962, there were 9 “induced mutant” cultivars. In 1969, there were 77, and 1,200 by 1990. As of 2008, more than 2,700 varieties resulting from mutagenic experiments have been released. Some were induced by x-rays, and some from chemical mutagens, but most from gamma-rays identical to those produced in the gamma gardens of the midcentury.

The gamma garden at Brookhaven, eerily resembling the radiation hazard symbol.